Freedom of Movement: Municipal Art Acquisitions 2018

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

25 Nov 2018 - 17 Mar 2019

The twenty artists participating in the exhibition Freedom of Movement: Municipal Art Acquisitions 2018 take varying approaches to this theme. While several focus on how the act of crossing a border has changed due to advancements in technology, others look at the daily lives of immigrants and how the body itself can limit mobility. Other works consider the legacies of migration, genocide, and statelessness, and the cultural biases embedded in disciplines such as mathematics. Artists also examine the creation and expression of cultural identity through objects, folk songs, and language. All of the participants in this exhibition ask viewers to reconsider their assumptions about civic engagement and responsibility, and to think about how we understand our neighbors, our environment, our world, and ourselves.

FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT CURATORIAL STATEMENT

By Karen Archey

A small boy, no more than three years old, is sprawled on a beach in a red shirt and blue shorts wet with saltwater. The lip of a wave overtakes his face, which is planted on the sand. Despite how peaceful and innocent he looks, he is unmistakably deceased, washed ashore as if a piece of jetsam.

We all know this image—it has been seared into the minds of nearly everyone in the world who follows the media. It portrays Alan Kurdi, the Kurdish-Syrian boy who passed away on September 2, 2015 during his family’s voyage from Syria, where their Kurdish-majority city had been taken over by ISIL. The photo quickly became a potent symbol of our geopolitical moment. It was picked up by news outlets around the world, reflecting both the human stakes of the refugee crisis and also a series of grave failures.

Having experienced life-threatening oppression in Kobani, the Kurdis travelled to Turkey to escape persecution. After their asylum application to Canada was rejected, the family paid a smuggler more than 5,000 euros for four places on a five-meter-long inflatable boat that would almost immediately capsize off the coast of Bodrum, Turkey. They were en route to the Greek island of Kos, only four kilometers away. Fleeing to Greece was a desperate option, but one that would ensure their safety—or so they thought.

“Freedom of movement” is a phrase that describes the right of a person to travel within a country, or to leave that country and later return to it. It was adopted by the United Nations in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and can be applied to those who are jailed within their own nation or who seek to travel abroad, whether as a refugee, immigrant, or vacationer. The term rose to prominence during the recent refugee crisis, when the world first became subsumed by a seemingly endless flow of stories about migration. Every day, we learned about the formidable journeys undertaken by refugees from Syria, Kosovo, Eritrea, Afghanistan, Albania, Iraq, and other Balkan, Middle Eastern and African lands, and the nations, such as Germany, that welcomed them, or sought to stem their influx.

As someone who migrated from the United States to Germany relatively easily in 2016, I became acutely aware of the power of my American passport. Prior to this, freedom of movement had meant to me, simply, the ability to choose where I wanted to live. As the events of that year unfolded, I began to interrogate the assumptions underlying that thinking. The sheer luck of being a white American woman gave me access to freedoms that Alan Kurdi did not have—ones that likely would have spared his life. While his death took place thousands of kilometers away, I came to grasp the ways in which I was implicated in his story. Where and to whom we are born is arbitrary, but no country exists in isolation, and particularly not at this moment. As citizens, we must understand how we fit into a larger story, and what histories and systems have contributed to the creation of our specific national and individual narratives.

An understanding of how we as individuals are implicated in geopolitical events is a theme of the work of artist Yael Bartana, whose 2017 film Tashlikh (Cast Off), is included in the exhibition Freedom of Movement. The title refers to the Jewish ritual of casting items into a river to atone for one’s sins. For her film, Bartana invited survivors and perpetrators of the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide, and the current ethnic cleansing campaigns in Sudan and Eritrea to discard items connecting them to these events. In mixing the belongings of people from both sides of each conflict, Bartana’s work suggests that recognizing and making amends with the past is arguably our obligation to the world and to our own civic sphere.

My initial understanding of freedom of movement—as pure possibility—failed to acknowledge that my reality was not universal, and that it was deeply determined by privilege, which is embedded in race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, and ability. As the work of artist Rory Pilgrimattests, absolutely everyone is affected by privilege, whether we acknowledge it or not. Through the collaborative production of concerts, music videos, and albums, Pilgrim creates environments of care and mutual support in which people from diverse backgrounds can come together and express themselves.

In a similar vein, for his ongoing project New World Summit, artist Jonas Staal organizes what he calls “alternative parliaments” that highlight the perspectives of people and groups who are stateless, blacklisted, or otherwise excluded from democratic processes. As we see in these works, privilege can emerge from history or biology, luck or socialization, and it shapes every aspect of our lives. It influences how a white man might unconsciously view himself as more deserving than a black man, or how many public spaces inadvertently exclude people with disabilities by not making architecture accessible.

While privilege is a topic often examined by those who lack it, it is equally—if not especially—important to consider it from positions of power. Basir Mahmood’s film Monument of Arrival and Return focuses on train station porters in Pakistan, a profession that became widespread while the country was under colonial rule. For the film, Mahmood instructed a local production company to film the men carrying objects from his house, calling into question both his status as an author and his economic position in relation to the porters.

In a more conceptual vein, the work of artist Falke Pisano traces how “otherness” has been historically produced through language and the natural sciences. Through deep readings of literature and historical texts she examines how tenets of Western thought—from scientific precepts to mathematical principles—grow out of particular socioeconomic and cultural contexts. While it may be tempting for some to view all of this as part of a conversation about identity politics that only pertains to certain groups, educating ourselves about the role of privilege is central to the work of understanding ourselves in the world—and to understanding how, for instance, the ability to travel freely is bound with opportunity and social mobility.

A REPOSITORY OF MEMORY

How we come to understand ourselves in relation to others, particularly in terms of national identity, is a process we all participate in. Gloria Wekker, Emeritus Professor of Gender and Ethnicity at Utrecht University, discusses this idea through the notion of the cultural archive, a term popularized by postcolonial theorist Edward Said. The cultural archive is a collective store of stories, sayings, and other forms of knowledge that individuals use to measure and validate their existence in the world. It is “a repository of memory,” Wekker writes in her 2016 book White Innocence. It exists “in the heads and hearts of people in the metropole, but its content is also silently cemented in policies, in organizational rules, in popular and sexual cultures, and in the commonsense everyday knowledge.”1

It is difficult to fathom how entrenched the cultural archive is in our daily lives, and how deeply the legacy of colonialism is embedded within it. Take, for example, the simple practice of drinking coffee in the morning, which millions of Dutch people do every day. This can be traced back to the eighteenth century, when colonial plantation owners in Java, Indonesia, helped the Dutch colonial government build an international coffee trade on the backs of exploited Indonesian workers. Similarly, in England, the national affection for black tea stems directly from the country’s colonial history in India. English tea is even prepared with sugar and milk—the same way as Indian chai. While connections may go unnoticed, many aspects of daily life in the Netherlands, Wekker writes, are “based on four hundred years of imperial rule.” The heart of her argument is that European identity was foundationally altered by colonialism and slavery—even as these histories are typically dismissed as having occurred long ago, on lands far from Europe.

Of course, the cultural archive also shapes the lives of those who have historically not been recognized within it. The work of artist Danielle Deanconsiders the history of colonialism through contemporary modes of identification, and particularly through how advertisers target different groups on the basis of race and class. In their work, Joy Mariama Smithalso explores less recognized dimensions of racism by examining how affects such as anger and cuteness are imposed upon black people, whether in everyday conversation or in popular media.

Discussions about the enduring effects of colonialism in the Netherlands have been incredibly politically divisive. As my colleague Jeanette Bisschops observes in her essay for this exhibition, recent initiatives to come to terms with the country’s colonial history, such as the movement to abolish Zwarte Piet, the work of the political party BIJ1, and the release of Wekker’s book, have sparked debates about the widely unacknowledged yet fiercely defended sense of white centrality within Dutch cultural identity. The work undertaken by Wekker and other Dutch decolonialists could be sidelined as only pertinent to minorities, but it is in fact key to arriving at a more holistic understanding of Dutch identity. This is especially true as one in six Dutch people have migrant heritage, and the city of Amsterdam itself is home to over 180 different nationalities.2&3 Given this, it is a wonder that the popular conception of a Dutch person in the Netherlands is that of a white person of Christian descent.

The work of Deniz Eroglu showcases the effects that narrow national assumptions can have on people from diverse backgrounds. Eroglu was born and raised in Denmark with a Danish mother and a Turkish father, and his work poignantly and sometimes humorously deals with the stereotypes imposed upon him in his home country. Eroglu’s experience is not an isolated one, and to many first- and second-generation immigrants, it is indeed familiar. Despite the fact that millions of people around the world grow up speaking Western European languages and absorbing the cultural norms of societies thousands of kilometers away, within those countries themselves, they are made to feel “other.”

Deniz Eroglu, 'Baba Diptych', 2016, 2-channel video installation, 2 minutes, 41 seconds and 1 minute, 58 seconds, courtesy the artist.

The patterns of exclusion are sensitively explored in Brussels, 2016, a film by Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide). Shot during the aftermath of the Belgian capital’s 2016 terrorist attacks, the film is structured around a letter to the artist’s mother in South Korea, bringing a personal lens to the enduring legacy of Western imperialism in daily interactions.

These are only two examples of the ways in which our world is increasingly interconnected. If we were to consider the notion of freedom of movement expansively—to include not just issues of migration but also the history of colonialism and the power structures that shape our respective views—we could arrive at a vocabulary that facilitates a broader sense of communal empathy and civic responsibility. As a public art institution, the Stedelijk is primed, if not obligated, to host these kinds of discussions by exhibiting works that address these social issues. Politics has reached an impasse, but aesthetic experiences may still have the potential to impact our thinking.

Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide), 'Brussels, 2016', 2017. Digital film, 33 minutes, courtesy the artist.

One might question how an American curator came to organize a Dutch national exhibition that focuses on such sensitive issues. As a white woman who is also a foreigner, I have simultaneously both an insider and outsider’s perspective. I moved from Berlin to Amsterdam to begin working at the Stedelijk in April 2017, and since then, I have felt that the Netherlands—as much if not more so than other Western countries—is struggling with issues relating to race, gender, feminism, and ability. While the fierce debates and efforts begun by Dutch activists are starting to alter the everyday fabric of life in the Netherlands, so too has there been a global uptick in open racism, ableism, and sexism—the kinds of sentiments that never would have been expressed publically with such impunity until recently. Increasingly, this kind of rhetoric is bound up with populist policies that discriminate against those who support them. Verena Blok’s video Robota captures this paradox, depicting two Polish brothers who regularly travel to the UK to make extra money as migrant construction workers, as they support the isolationist policies of an increasingly nationalist Poland.

Verena Blok, 'Robota', 2018, single-channel video and sound installation, 12:30 min, courtesy the artist and Mondriaan Fund.

THE MUSEUM AND THE CULTURAL ARCHIVE

As a city-subsidized museum frequented by school classes, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam plays a key role in cultural memory formation, and by extension in the creation of Dutch identity. As a nearly 125-year-old institution that houses the largest collection of contemporary art and design in the Netherlands, the Stedelijk represents the creative output and cultural face of the city of Amsterdam—a crucial part of the Dutch cultural archive. Every two years the museum stages the Municipal Art Acquisitions, a themed, municipality-funded exhibition with the aim of acquiring high-caliber work from artists working in the Netherlands. In this edition, I wanted to expand on the very notion of “Dutch talent,” a recurring talking point within the Netherlands, and create a theme for the open call that would foster urgent conversations about Dutch cultural identity.

The jury was also particularly receptive to works questioning the authority of art institutions. By creating vivid yet freely accessible websites, artist Rafaël Rozendaal does precisely this. Similarly, through his audio surveillance project Institute, Remco Torenbosch highlights the tension between the Stedelijk’s galleries—the public face of the institution—and its private offices, where conversations about the exhibition and purchase of artworks take place.

Nearly four hundred artists living in the Netherlands responded to the museum’s Municipal Art Acquisitions open call. Over the course of reviewing submissions, it became abundantly clear that many artists, and particularly those from less privileged and subaltern backgrounds, did not take inspiration from the theme “freedom of movement,” but rather saw it in terms of a lack. Their creative strategies were often confrontational. These submissions contrasted starkly with the work of artists from white backgrounds, who frequently used fables and other abstractions to explore freedom of movement. The task of the jury was to represent the best of both of these approaches, and to find a bridge between them.

The range of interpretations prompted many fascinating discussions among the five-person jury, which consisted of artist Harm van den Dorpel; choreographer Ligia Lewis, who performed her work minor matter at the Stedelijk in July 2017; performance curator Susan Gibb; Sandberg’s Shadow Channel course director and musician Juha van ‘t Zelfde, and myself. Over three days of in-person interviews last March, our list of artists was whittled down to twenty.

Jurors took care to craft an artist list that speaks to the diversity of the Netherlands while also recognizing how historical and political circumstances have prioritized certain people over others. This was not a simple task. It is noteworthy that an overwhelming number of applicants—over ninety percent—were white, middle-class artists. This does not reflect the composition of Dutch society as it showcases the fact that the Stedelijk has traditionally defined itself within the parameters of a certain idea of Dutchness. In retrospect, it makes sense that artists of certain backgrounds would not apply to an open call when they have historically not seen themselves reflected within the museum.

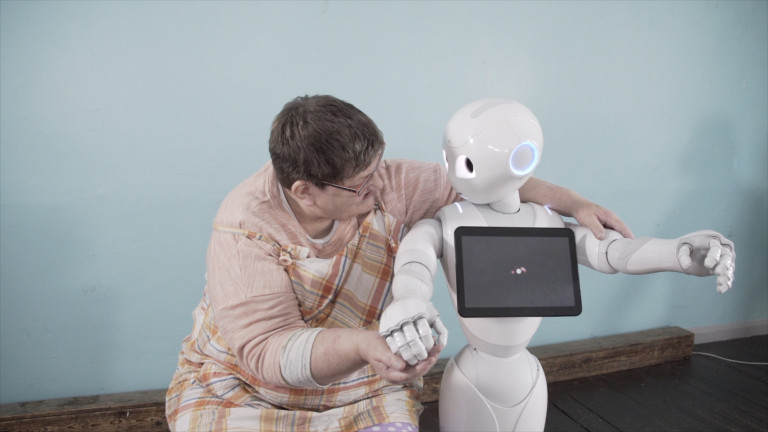

In addition to the theme, this year’s edition of the Municipal Art Acquisitions is also organized around “time-based media,” which generally designates works that are video, slide, film, audio, performance, or computer-based. In this sense, the exhibition title refers to the movement of images. The field also includes choreography and dance, such as Michele Rizzo’s work HIGHER xtn., which explores how dancing in a nightclub can become a transcendent, almost religious experience. Over the course of working on the show, I came to view time-based media as particularly well suited to address the political issues considered within the exhibition. In his three-channel video installation Non-Linear Trajectories, Juan Arturo Garcíacombines audio narration with 3D scans of the Dutch Immigration and Naturalization Services office to comment on the stressful and unpredictable experience of immigration—as well as the tensions that are mounting at borders around the world.

Photographic mediums are key to telling stories of migration, as we saw with Alan Kurdi. Yet engaging with the various dimensions of migration is not only a matter of capturing discrete moments. Artist Angela Melitopoulos has written incisively about the disjointed nature of the migrant experience, the shock of leaving behind one reality only to arrive at a new, oftentimes conflicting one. She writes:

As a migrant one lives in a world of differences, singularities, heterogeneities (the “here” that one has migrated into and the “there” that one comes from; the mother tongue and the language that has to be learned and the culture that has to be adapted). One lives several worlds at the same time, but cannot reduce them to one world: they have to be allowed to exist simultaneously… Through the movement situation of migration, a way of thinking developed with photography, film and video technology that must comprise the spaces of imagining and the dimension of distribution, which records journeying, here/there narratives, and processes of de- and re-territorialization. Image production is a vital mechanism of migration, because movement is communicated through it and it is constituent for the spatial relationships of diaspora.4

According to Melitopoulos, it is the very act of video editing that allows for the multiple, divergent truths with which every migrant must contend to be shaped into aesthetic form. Crucial to Freedom of Movement is an artist’s ability to create narratives that unfold through time to represent not just their own personal stories, but that of a shared experience.

Thanks to increased political awareness in the West brought on by movements such as Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and “Kick-Out Zwarte Piet,” the realities that have always been true for migrants are now becoming universalized. Since the advent of the internet and handheld consumer technologies such as the smartphone, we have an increasingly close relationship to the now 24-hour news cycle. The consumption of news is addictive, and is changing the way we see the world. It is also changing how reality is mediated. Neither of Us is Powerless by artist Jort van der Laan, for instance, focuses on the various technologies that exist within airports, from sophisticated retinal scanning machines to simple massage tables that serve as a means of distraction. Meanwhile, in their work, media art pioneers JODI comment on how our cellphones actually function as quotidian surveillance devices, while Melanie Bonajo highlights how what happens online can bear very little relation to what’s actually going on in the world. In her film Progress vs Sunsets: Reformulating the Nature Documentary, she questions why we love viewing images of animals on the internet—even as we subject them to poaching and deforestation.

The themes in the exhibition range widely, yet several of them touch upon the biological implications of our troubling historical moment. The sculptural works of Isabelle Andriessen, for instance, reimagine the human body in the wake of environmental collapse. Kate Cooper’s computer-generated animation work Infection Drivers considers how the vitality of the human body is dependent on a set of internal processes that contain the potential to go awry. But even if our environments can betray us, even transform us, they can’t completely determine our future. A sense of optimism in dark times can perhaps been seen most explicitly in the work of Dutch-Russian artist Polina Medvedeva, whose film The Champagne Drinkers celebrates the informal car service economy in Russia, and the ingenuity with which its unlicensed taxi drivers manage to make a living during times of hardship.

All of the artists in Freedom of Movement ask viewers to reconsider their assumptions about civic engagement and responsibility; how we understand ourselves, our neighbors, our environment, our world. Their works are essential contributions to both the national cultural archive and to the very idea of what it means to be Dutch. At the same time, many of the issues that this show grapples with are also global. The artists here offer perspectives and insights that remind us that freedom of movement is not only about the experience of migration or the pleasure of travel—it reflects upon how we think about what it means to be human, and the rights that accompany this, or not. Having previously assumed that freedom of movement was simply a thing to be taken for granted, through this exhibition I have come to realize that it is often quite the opposite—a liberty for which we must fight.